Grand Ideals and the Travails of the Plains

European integration is a project for Sunday sermons. It deals with grand ideals and noble goals such as peace, freedom, democracy, the rule of law, solidarity, prosperity and stability. And indeed, for all its weaknesses, the European Union and its predecessors (European Coal and Steel Community, European Economic Community, European Community) have been extremely successful in promoting these values. It has been successful because it takes a very long-term view and has facilitated its Member States to constantly search for “common ground” and find compromises in the spirit of shared values.

From the point of view of individual freedom and also in economic terms, the EU’s great achievement of recent decades has been its consistent efforts to gradually establish an area of freedom, security and justice, with respect for fundamental rights and without internal frontiers, in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is ensured within the internal market.

In terms of foreign and security policy, it is a great gain that a large proportion of European countries are integrated into a common political structure. The current geopolitical situation gives reason to consider the closer integration of other, especially Eastern European states, more seriously than before.

However, it is here at the very latest, that the hard slog, or in Brecht’s words the “travails of the plains” begins: Past rounds of enlargement as well as the very varied economic development of the EU Member States have made the EU more heterogeneous which tends to hamper the process of building “an ever closer Union”. It also makes it harder to identify a common culture of respect for the rule of law and democracy. In line with the EU’s motto “United in diversity,” one can accept this heterogeneity and still be of the opinion that it is more manageable within the common structure of the European Union than outside.

Although the EU enjoys a high level of public trust, its policies are perceived as overly complex and its decision-making processes opaque, with decisions taken by faceless “eurocrats”, remote from the every-day problems of ordinary citizens and businesses, on the notorious “Spaceship Brussels.” Although many citizens identify with the goals and achievements of the EU, they are unlikely to identify much with the individuals on the EU’s political staff. The political machinery of the EU is unfamiliar to many.

While many support the EU’s overall objectives, there is often a suspicion that the EU regulates too much and in an unnecessarily bureaucratic way. In the current more complex situation, it will not be easy for the EU to rely on its previous successes. Its great success has made it the focus of populist tendencies and the very nature of the EU may make it particularly vulnerable in this regard. But even in this situation, the EU should hold on to the secret of its success: A deep breath and the art of compromise.

This article aims to shed light on the mysterious paradox of the European Union: It argues that there are a number of characteristics of the European Union – technocratic regulation, package deals, immunity to political change, the complex structure of regulatory entities – which at first sight appear disadvantageous to its political functioning but, in fact, are precisely what have facilitated consensus-building among Member States, thereby making the EU so amazingly resilient and successful over the long term. Against this background, we then take a brief look at the future challenges for the EU in this respect.

Positive Image of the EU

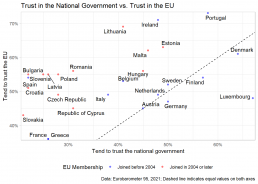

The population of the European Union has a largely positive perception of the EU. According to a Eurobarometer Study, in many Member States, trust in the European Union is higher than trust in national governments (notable exceptions: Denmark, Finland, Germany and Luxembourg, Eurobarometer, Data as Excel sheet). Trust in the EU tends to be higher in the Member States that have joined since 2004 than in the older Member States. These countries also tend to have lower levels of trust in their own governments.

Only among the older Member States do some have above-average trust in their own government and below-average trust in the EU. Only among the new Member States do some have above-average trust in the EU but below-average trust in their own government.

According to the same 2021 Eurobarometer Survey, 45% of those surveyed see the EU in a positive light (70% in Ireland and 33% in Greece). At the same time, trust in the European Union appears to have been higher than trust in national governments and national parliaments over a period of more than 15 years. In 2021, 49% of EU respondents say they tend to trust the EU (national governments: 37%, national parliaments: 35%).

The EU’s trust advantage over national governments could be due to the following reasons: First, the comparison is asymmetrical. It compares trust in a government with trust in an association of states with executive, legislative and judicial powers. While governments are likely to be thought of very much in terms of people and the government of the day, the EU is thought of in terms of ideas and their long-term outcomes. Second, government action is much more partisan than EU action. It is therefore seen much more in terms of ideological conflict.

Reservations about the EU

Despite the fundamental trust that the EU seems to enjoy, there are still reservations about the EU as a political organisation that can be exploited for populist purposes. The impression is created that the EU is a project of technocratic elites, in which baffling and unnecessarily complicated rules are enacted through almost incomprehensible decision-making channels by virtually unknown actors.

The EU is difficult to understand. It is not easy for the layman to understand what the EU is responsible for and how exactly the decision-making process works. It is also difficult to assign political responsibility and to react (approve or disapprove) to political results in elections.

Few citizens are likely to be constitutional experts on their home state and will therefore also find it difficult to pinpoint the constitutional competences of their own governments. However, familiarity and political folklore tend to mask this problem and give citizens the feeling that they know their way around.

EU is Different

The way the EU works is difficult to understand from the outside. It is true that there are certain similarities in the responsibilities and distribution of tasks between the parliaments and governments of the Member States, on the one hand, and the European Commission and the European Parliament, on the other. But the differences are considerable.

- The EU’s legislative powers are limited. It can only act where the Treaties endow it with competences.

- The democratic legitimacy of the European Commission in general, and the college of commissioners in particular, is only very indirectly based on a direct vote of the electorate.

- The European Parliament is one of the most powerful parliaments in the world – but it cannot initiate legislation itself nor therefore set the political agenda.

- The European Parliament is not organised along traditional lines of conflict between government and opposition. Consequently, individual members of parliament can play a much more influential role than their national colleagues in organising very productive cross-party cooperation. However, this can also lead to a lack of polarising parliamentary exchanges with a high public profile.

- Executive responsibilities are dispersed among a large number of agencies and various networks of national regulators, in addition to the European Commission. On occasion, this is also referred to as the Eurocracy.

Moreover, EU policy may appear to operate largely independently of political and changing preferences. Member State governments change, the ideological orientation of national politics changes – and the EU just carries on, or so it seems.

The politics of the Member States is characterised (to put it simply) by the alternation of more left-wing and more right-wing governments. The change of leaders symbolically heralds a (more or less pronounced) change in the ideological orientation of politics. It gives citizens the impression of responsiveness to their wishes and a sense of progress.

Things are different in the EU. Leadership changes do happen, but they are far less likely to be seen as a symbolic way of announcing political change. Many leaders simply lack the popularity to do this. Nor is there a sense that there has been a clear change in policy-making at EU level, for example as a result of the elections to the European Parliament.

These preceptions may be correct to some degree. However, it is worth putting them into perspective and looking at the relationship between these peculiar characteristics of the EU and the success of its Sunday speeches.

Is EU Legislation Overly Complicated?

The European Union enacts a great deal of legislation that is rightly perceived as complex. This applies in particular to the many conditions that must be met for goods and services to be marketed in the internal market. EU law ensures fair competition in the internal market and the possibility of shaping what happens in the internal market in line with political priorities, for example on environmental and climate change issues.

Yes, the EU adopts a lot of legislation of a regulatory nature. This is because the EU has been endowed with competences to regulate many issues so that goods and services can be traded freely in the internal market. In addition, many cross-border environmental and climate protection issues are better dealt with by the EU than by individual Member States. In other words, the EU regulates areas that would otherwise be regulated less effectively by the Member States. In this sense, one can legitimately argue that, overall, EU regulation eliminates the need for even more legislation as, otherwise, there would probably be up to 27 different national regulations.

Complex rules may even be appropriate. After all, issues are often complex today. Some regulations may be better or worse at achieving certain objectives. Minimising complexity is only one criterion among many.

However, the accusation of technocratic and complex EU regulation overlooks the fact that Member States are also capable of adopting technocratic regulations. If the EU did not have certain competences, this would not mean that Member States would remain inactive. But in the diversity of national policies, with their strong emphasis on personalisation, the technocratic character of regulation is perhaps less noticeable than in the EU.

Complex Structure of Regulatory Entities

The executive and regulatory functions of the European Union are not the sole responsibility of the European Commission; regulatory competence is, in fact, distributed among various bodies, including European agencies and regulatory networks of national regulators.

While it may seem intuitive to assume that the EU’s regulatory initiative on a particular issue lies solely with the European Commission, agencies now often exercise considerable regulatory power by providing specialized expertise, monitoring compliance, coordinating information exchange and facilitating research and training.

The EU also relies on decentralised regulatory networks of national regulators to provide technical expertise and knowledge in a number of policy areas, particularly where national authorities have significant regulatory experience or specific expertise.

The complexity of the regulatory structure (EU Commission, agencies, networks) does not seem to be justified (only) by objective expediency. In fact, there are indications that this regulatory structure is the result of a compromise between conflicting interests. It can be assumed that both the European Commission and the European Parliament would in principle prefer the Commission to have regulatory competence. However, Member States are often reluctant to transfer competences to the Commission. By locating them in European agencies, or by ensuring loose regulatory coordination within networks of national regulators, they retain greater control over regulation.

The establishment of regulatory networks in the EU may create a state of suspense in which regulatory issues are inadequately resolved due to a weak transfer of competences. Conflicting interests underlying a compromise may be suspended in the Hegelian sense. This situation can either lead to the weak coordination of regulation desired by some actors or become a gateway to a stronger exercise of competence by the EU. The unsatisfactory situation may justify further attempts to transfer more responsibility to the EU.

EU’s Perseverance

One of the EU’s strengths is its persistence. Time and again, it succeeds in pursuing its chosen strategies over a long period of time, even in the face of opposition.

By contrast, the policies of Member States are much more geared to electoral cycles and changing majorities. Governments start with a specific programme, are judged on their performance and are confirmed or voted out in elections. New governments are free to set their own priorities and break with the policies of their predecessors. It is a normal expectation in democracies that new governments will do things differently from old ones.

Things are different in the EU. There are probably two main reasons for this. First, the EU is bound by its treaties to take on certain tasks. You cannot give a supranational organisation tasks and then expect it to do nothing. Second, the Heads of State or Government convening in the European Council define the EU’s policy priorities by consensus. On this basis, the European Commission prepares its legislative proposals, which are then adopted by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union.

Even in the event of opposition in the legislative process, the Commission (and other actors) can refer to the consensual decision of the European Council. Going against a unanimous decision of the Council in public could cause a massive loss of reputation for the EU. The political costs are therefore high. Formally, it is difficult to reverse a Council decision once it has been taken. This would again require unanimity. So once there is a mandate from the European Council, the forces of inertia are considerable and the political costs of public opposition are high.

These forces of perseverance enable the EU to continue on a course once it has been set, within the limits of its treaty powers, even if the majorities in the Member States change and the political priorities of their governments and parliamentary majorities evolve.

It is this staying the course that is the key to the EU’s long-term achievement of its major goals.

A Challenge: Increasing Heterogeneity

In the past, the EU has worked relatively well at finding compromises. Even if the interests of the Member States in the EU were never congruent, they were relatively similar in the first decades of the EU. With its various enlargements, the EU has become increasingly heterogeneous. And the Member States have developed very differently over the last twenty years. This is a challenge for the EU’s future ability to find good compromises.

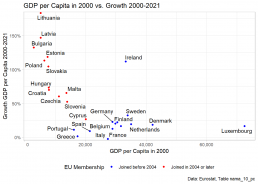

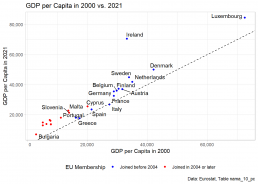

In 2021, the EU is more heterogeneous in terms of GDP per capita than it was in 2000. This heterogeneity is due to the accession of new countries from Central and Eastern Europe, which generally have a lower GDP per capita than the older Member States. Furthermore, different growth patterns between old and new Member States contribute to this heterogeneity. The new Member States have experienced above-average growth rates, with a tendency towards higher growth in those countries that had a lower GDP per capita in 2000. This allows them to narrow the economic gap with the established Member States. However, the older Member States have on average lower growth rates, with Member States with a higher GDP per capita typically showing higher growth rates than Member States with a lower GDP per capita. This leads to diverging trends within the group of older Member States.

Italy’s GDP per capita in 2021 is lower than in 2000. Greece has roughly the same GDP per capita as at the turn of the millennium. Growth in Portugal and Spain has been low. Ireland, with its terrific growth rate, is certainly an exception. But we also see above-average growth rates (among the older Member States) in the comparatively wealthy states of Sweden, Germany and Finland.

The enlargement of the EU and the resulting increase in structural heterogeneity, combined with growing divergence within the older Member States, has made reaching a compromise more difficult. But this does not mean it is impossible, rather that it may lead to solutions that are more complex and harder to understand.

Outlook

As long as the EU pursues its objectives in a credible manner, its reputation will endure. But the complexity of its rules, political bargaining, the division of regulatory responsibilities and a certain stubbornness are the very characteristics which allow the EU to achieve its goals. Unfortunately, these characteristics also make the EU increasingly difficult to understand, which could threaten the EU’s credibility in the future. While it is impossible to abandon these distinctive EU characteristics, communicating them is essential to maintaining transparency and trust. It is crucial to engage in critical and controversial debate on policy issues within the EU, but highlighting these characteristics should not be used to discredit the EU – at least not until there is concrete evidence that an alternative approach is more effective.

For the foreseeable future, the EU will be characterised by some degree of heterogeneity between Member States. Possible enlargements will increase this heterogeneity. The art of compromise will therefore become all the more important. The characteristics of the EU are therefore likely to remain with us for some time to come.

More about Democracy in Europe:

Copyright Header Picture: European Parliament (Eric Vidal)

Copyright Picture Author: cep

Könnte Sie auch interessieren

9. Juli 2024

Konstantin von Notz : „Es ist Zeit, unsere Demokratien sehr entschlossen aufzustellen“

Er steht seit diesem Jahr an der Spitze des Geheimdienstausschusses des…

1. Juli 2024

European Parliamentary Elections: A Debacle for Pro-EU Parties or Their Last Chance?

Between 6 and 9 June, 400 million Europeans voted in the European Parliamentary…

24. Juni 2024

Dissolution of Parliament: Good or Bad for Democracy?

An hour after the results of the European elections, Emmanuel Macron announced…