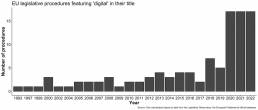

After Europe has long slept through the digital revolution, the European Commission is determined to lead the continent into a Digital Decade and to become a global standard-setter for the internet. The Covid pandemic was a massive wake-up call to promote and regulate digital solutions. Since then, hardly a week goes by in which newspaper readers do not come across a new initiative by the European legislator: The Commission formulates new product requirements to boost its cybersecurity, regulates crypto-assets and data access, responds to growing concerns about disinformation with a Media Freedom Act, and proposes, through the combined Digital Markets and Services Acts, common rules of the game for virtual competition and discourse, to name but a few. It is highly welcome that Europe now wants to expand its digital sovereignty and set its standards instead of following others – but the chosen path might not lead there.

The recent European activism runs the risk of remaining stuck in narrow, sectoral thinking, as the multitude of legislative projects and directives is slowly but surely becoming ever more complex, confusing, and potentially contradictory. It is unclear how the new obligations for large platforms fit into the broader regulatory context, resulting in various substantive, procedural, and institutional difficulties. For instance, there is a looming conflict between the EU’s high privacy standards and rigorous competition law reforms. Regulators and firms face conflicting goals in the European attempt to establish a digital single market that is expected to feature leading firms, open markets, transnational data flows, high privacy and security standards, as well as prolonged economic growth – all simultaneously.

On top of this, European institutions have ongoing internal conflicts about the appropriate ethical and legal framework for specific applications of Artificial Intelligence. A recent survey of the EU’s digital agenda finds a “significant risk” that inconsistencies in the developing regulatory framework and conflicting policy priorities may hinder the continent’s digital revolution. Finally, the sheer mass of legislative documents and accompanying reports poses problems in itself: Large law firms are increasingly hiring computer scientists and hosting high-priced legal tech events to provide meaningful structure to the deluge of rules. Without a common political denominator and regulatory coherence, all that remains of the grand vision of a Digital Decade is a mass of over-detailed and under-enforced rules. To avoid this scenario, a holistic order-political perspective is required.

Technology as a question of order

Those looking for such a perspective might find it in the Freiburg School, which goes back to the economist Walter Eucken. His ordoliberal concepts influenced not only Germany’s post-war social market economy but also the economic rules of the emerging European community and, later on, the competition law language of the Commission and the Court of Justice. Just before his unexpected death in 1950, Eucken wrote an article on the relationship between technology, concentration, and the proper ordering of the economy, whose reasoning offers a surprisingly up-to-date guiding post for the digital age: “The tension between increasing competition and its resistance is a fundamental fact of recent economic history,” Eucken writes. He feared that large, automated firms would follow their incentive to monopolise and gradually acquire more power over contractors, employees, and politicians, implying that the market economy would eventually eliminate itself. To counteract the anti-competitive behaviour of powerful firms and their vested interests, he and his followers envisioned an economic constitution centred on fair competition that would guide all areas of economic policy and complement a democratic society. Today, however, Europeans can follow, virtually in real time, how Eucken’s fears are coming true.

During Europe’s digital slumber, the commercial use of the internet has become entrenched in the hands of American and, increasingly, state-backed Chinese companies. Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft (GAFAM) in the West, as well as Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and Xiaomi in China, enjoy persistent market shares. They utilise their unparalleled possession of data to expand their services into ever more adjunct sectors like autonomous vehicles, FinTech, and even healthcare. As a global collective of researchers has recently concluded, the structural features of the resulting digital infrastructure contribute to echo chambers, polarisation, eroding trust in governments, and global spill-overs of unreliable information and local instabilities. In other words, these tech giants are not only market gatekeepers but also knowledge and information gatekeepers, a status they are currently cementing as thousands of European enterprises are basing their digital transformation on analytical tools provided by the cloud services of these digital giants. Ultimately, the power of Big Tech to manipulate economic behaviour and political information might threaten liberty and democracy as such, irrespective of the motives of individual entrepreneurs.

EU digitalisation policy from an order-political perspective

One of Eucken’s most compelling insights is that the economy is not subject to some isolated law of supply and demand but that society as a whole is evolutionary and interdependent, which needs to be reflected on the level of policy- and law-making. When applying this perspective of the “interdependence of orders” to the EU’s current attempts at digital regulation, it seems that many – if not all – of these reforms can be usefully linked through an ordoliberal perspective that regards power as the main problem and disempowerment as the only viable remedy.

This is most evident in the Digital Market and Services Acts, which specifically target influential “gatekeepers” and “large online platforms” and assign them a specific responsibility for ensuring a level playing field for businesses and a safe digital space for users. This echoes the “special responsibility” to compete exclusively on the merits that EU competition case law places on dominant firms already today. Similarly, Commission officials involved in the plans for an EU Data Act have hinted that they were motivated by the idea that data should not continue to go to those who already have plenty of data. The envisioned legal framework for FinTechs includes a separate chapter to prevent market abuse related to crypto assets. And with its proposal for the European Media Freedom Act, the Commission is responding not only to the dangers posed to journalists by government malware but also to the concentration of media ownership in a few hands. Finally, when unveiling the Commission’s plan to regulate the metaverse next year, Single Market Commissioner Thierry Breton vowed to avoid a “new Wild West or new private monopolies.” Eucken could not have said it better.

Besides streamlining the current wave of digital policies along a single vision, ordoliberal ideas help to formulate additional policy demands. Eucken developed a sensible response to the commonly heard defence of today’s Big Tech companies, according to which their dominant position is simply the inevitable result of scale and network effects, big data, and winner-takes-all markets: “It is not the increase in the size of individual industrial firms, which takes place in the course of technical development, that is decisive,” he noted in 1950, “but the domination of many firms by one individual entity.” From this perspective, it is alarming that European competition authorities did not block one of the more than 400 acquisitions by GAFAM between 2010 and 2021. The power of Big Tech must therefore be integrated into the substantive scope of EU data protection and consumer law and supported by asymmetric enforcement of these rules. For instance, stricter merger control in line with ordoliberal priorities would help prevent the emergence of new gatekeepers regarding virtual assistants, which have become powerful consumption and information intermediaries.

Following Eucken’s fears, scrutiny should be extended beyond specific products or ecosystems and consider the extent to which the EU should accept concentrated, interlinked power as such. The current debates about Tesla boss Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter and his handling of the Starlink system in Russia’s war against Ukraine are the latest examples of what happens when politicians and regulators become too narrowly focused on markets while disregarding the interdependence of the economic order with other societal spheres, like public discourse or national security. Since ordoliberals perceived this competition-democracy nexus early on and influenced the normative underpinning of the EU legal order with their vision of an economic constitution, their thinking contributes to the current debate on more political antitrust in Europe. More generally, a progressive ordoliberalism suggests that the EU’s regulatory agenda in the digital age should be oriented towards the overarching goal of maintaining a democratic and free society in the face of the immense power wielded by Big Tech. Ultimately, this will make the European digital space more resilient.

Ordoliberalising the digital space boosts European resilience

In times of new global disorder, aligning the EU’s digital regulation with the ordoliberal perspective about power is the best way to protect our social and economic institutions from cyberattacks, financial crises, and other external shocks. Whereas over-detailed, sectoral rules reduce resilience by hindering standardisation, interoperability, and substitutability between different digital sectors, products, and infrastructures, a regulatory landscape focused on removing concentrated power promises a future in which shocks can be more easily absorbed and supply-side channels less likely disturbed. Nowhere has this become more apparent than in the semiconductor industry, where the damaging chip shortage results from the presence of quasi-monopolists and geographic concentration.

Eliminating such and other technology chokepoints will enable, in the sense of Friedrich Hayek’s “spontaneous order” theory, more competition activities that act as discovery procedures and thus further improve resilience through experimentation. Such a decentralised architecture of European digitalisation is undoubtedly in line with the initial vision of Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, who has recently warned that the web has evolved into an “engine of inequity and division; swayed by powerful forces.” A coherent and targeted mix of digitalisation policies along ordoliberal lines would reverse this trend, allowing the EU to achieve a true Digital Decade.

Copyright Header Picture: shutterstock

Könnte Sie auch interessieren

15. April 2024

Die Zukunft der Kriegsführung: KI im Gazastreifen

Technologie hat schon immer das Wesen der Kriegsführung neu definiert – heute…

15. März 2024

Biden’s Executive Order on AI and the E.U.’s AI Act: A Comparative Analysis

AI ethics initiatives are essential in bringing about fairer, safer, and more…

4. Dezember 2023

Digitale Brücken: Wie KI die europäische Integration vorantreibt

Durch den Einsatz digitaler Technologien, wie KI-basierter Simultanübersetzung,…