Prologue: On the idea of ‚European‘ progress

Today, as Europe seeks to define its own position in the face of global power shifts and digital transformation while striving for sovereignty, the following essay offers ideas for a common orientation that does not emulate autocracies but seeks to renew the strengths of its own order. It advocates a European understanding of progress that goes beyond market and power logic, strengthens diversity and enables creative participation. In this way, the European Union can remain not only economically strong, but also socially just, democratically resilient and culturally sustainable. Work and society are undergoing such fundamental changes that progress must and can be considered more comprehensively. For example, the demographic pension problem is currently discussed in very simplified terms as merely an extension of working life, and AI as technological productivity potential.

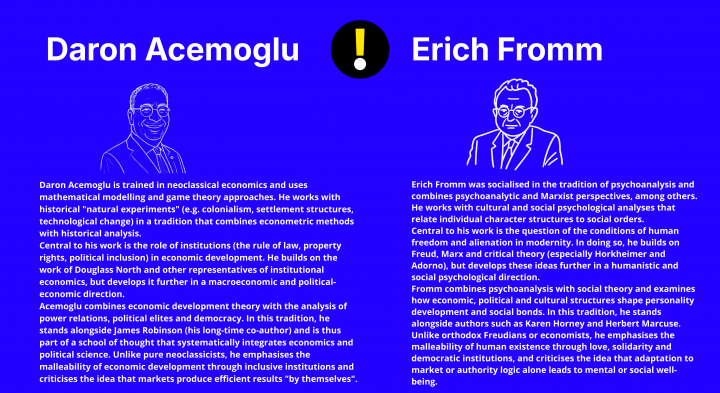

The essay „Work and Society in Transition: An Economic-Psychological View of Freedom, Progress and Humanity in the Thinking of Erich Fromm and Daron Acemoğlu“ addresses a central question of European policy: How can technological and economic change be shaped in such a way that it not only increases growth and efficiency, but also strengthens freedom, progress and humanity? The essay examines the concepts of freedom, progress and humanity in the thinking of Erich Fromm and Daron Acemoğlu and brings them into an interdisciplinary dialogue. While Fromm emphasises the socio-psychological and social conditions for human self-development, Acemoglu analyses the economic and institutional foundations for participation and innovation.

Together, both thinkers point out that technological and economic developments must not be an end in themselves, but must serve humanity and increase prosperity. The extent to which this happens depends – as Acemoğlu and Fromm show – on institutional and socio-psychological conditions, which are currently eroding more and more. The example of artificial intelligence shows that progress can only succeed if it simultaneously increases productivity and promotes humanity. The essay advocates an understanding of progress that focuses on freedom, dignity and creativity, thus offering an integrative benchmark for shaping work and society in the digital age.

Progress as a concept critical of structures

„We’re disappointed too. With consternation. We see the curtain closed, the plot unended.“ (Brecht, 1967)

Bertolt Brecht’s closing words from the play The Good Person of Szechwan (1967, p. 1607) express a feeling of helplessness that can overcome the audience when the curtain falls. Instead of receiving answers to pressing questions, many new ones suddenly arise. This is Brecht’s principle: theatre should not become a convenient consumer product where you leave your mind at the cloakroom like a coat and allow yourself to be entertained in the auditorium. Brecht’s theatre pedagogy – epic theatre – aims, on the contrary, to stimulate thinking and challenge the audience to critically reflect on social conditions. Such a theatre performance can – and should! – initially leave the audience feeling disappointed: they have not received the answers they hoped for. However, this disappointment should not be the depressing end, but rather the critical beginning.

The many unanswered questions, the disappointment at the lack of answers and the sober reflection on the state of the world certainly describe the prevailing mood of the present: „What is happening here – and where is it all leading?“ one might ask oneself helplessly in view of the changing political circumstances. Brecht suggests that we should not rely on ready-made answers, but rather think for ourselves, develop our own ideas and try to find honest answers to our questions. Brecht already establishes the connection between individual experience and social conditions, which in turn brings to the stage the discussion of how abstract structural conditions affect humanity in concrete terms.

This paper attempts to build a similar „bridge“ between abstract structural conditions and concrete humanitarian conditions by combining economics, political science and social psychology in an interdisciplinary manner, drawing on two thinkers who have adopted Brecht’s credo: the economist Daron Acemoğlu and the social psychologist and humanist Erich Fromm.

Erich Fromm and Daron Acemoğlu in dialogue

Erich Fromm and Daron Acemoğlu are unconventional thinkers: Acemoğlu combines neoclassical approaches with approaches from modern institutional economics, thereby integrating perspectives from economics and political science. Erich Fromm combines Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism with Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis, among other things. In their work, both scholars have created cross-connections between different disciplines, thereby linking psychoanalysis and political science via the connecting link of economics. And indeed, it seems that the significance of politics today, now that major upheavals are causing not only structural disruption but also cognitive dissonance, has taken on an almost psychoanalytical dimension.

Why do systems arise – or persist – that hinder rather than promote social progress? Acemoğlu analyses how institutions must be designed to enable participation and innovation, while Fromm asks about the psychological, cultural and social conditions for freedom, creativity and dignity. In a dialogue with both of them, we want to ask ourselves what a society looks like in which progress is not only technically measurable but also humanly experienceable.

Progress between structure and self-development

It is by no means the case that, as in the naturalistic fallacy, what is good will prevail. Nor is it the case that what prevails must also be good. Even in democracies and market economies, there are necessarily formal institutions and informal power structures that determine the nature of technical progress in work and society.

At a time when exponential technological innovations appear to be natural necessities and digital transformations are shaping social development, it is crucial to put people and their self-development back at the centre. Progress must not be measured solely in terms of efficiency and speed, but must be guided by whether it contributes to a successful human life. Current developments in particular, namely the increasing fusion of human and machine intelligence, involve not only a technological aspect of progress, but also an ontological and anthropological one. It is no exaggeration to assume that the technological upheaval brought about by artificial intelligence marks the transition to a new civilisation. Fromm and Acemoğlu share a common conviction: economic and technological progress must not be an end in itself. It must serve to build a humane society.

In his work The Sane Society (1955a), Fromm emphasises „that progress can only be achieved if changes are made simultaneously in the economic, socio-political and cultural spheres, and that any progress limited to a single area prevents progress in all areas.“ (p. 6) In Fromm’s view, a society that is technologically advanced but emotionally and socially impoverished cannot be considered civilisational progress. For him, progress without humanity is not only incomplete but potentially destructive.

Daron Acemoğlu focuses on the institutional prerequisites for social development. In Why Nations Fail (2014), he shows that technological innovation only leads to widespread prosperity when it is embedded in inclusive economic and political institutions. Where power, resources and decision-making authority are concentrated, only a few benefit – progress then becomes a driver of growing inequality. He writes:

„Inclusive economic institutions (…) create attractive conditions for the vast majority to participate in economic life and make the best use of their talents and abilities, and they allow individuals to make free choices. To be inclusive, economic institutions must provide security for private property, a neutral legal system and public services to create fair conditions that enable people to act freely and enter into contracts. They must also allow the creation of new businesses and allow their citizens to decide for themselves on their own career paths.“ (p. 106)

For Fromm and Acemoğlu, progress is therefore not purely a technological issue, but rather a question of the distribution of opportunities, participation and creative power. In modern societies, this issue is largely determined by the institutional framework, in which forms of power also manifest themselves. However, it is not only a question of power constellations that determine our development, but also a question of understanding individual freedom.

In Escape of Freedom (1941), Fromm distinguishes between two forms of freedom: „freedom from“ (responsibility) and „freedom to“ (the active development of the self). Fromm warns that people who have broken away from traditional authorities but have not found a new inner orientation can fall back into authoritarian systems by propagating the supposed advantages of „freedom from“ responsibility for the community in order to gain a false sense of security.

In To Have or To Be ? (1976), Fromm writes that it is a (mental) „leap“ to develop from the attitude of „freedom from“ to the attitude of „freedom to“. Mere rebellion in the attitude of „freedom from“ offers no social orientation. It offers no goal towards which one can „move“. On the contrary, the mere desire to „be free from restrictions and dependencies“ leads many into dependency (cf. p. 324). Free markets often preach the radical individualism of „freedom from,“ where everyone has to fend for themselves and no one acts for the community. In reality, however, few people benefit from this attitude, even economically, as Acemoglu shows in his research.

The concept of „freedom to“ (the active development of the self) is the real social challenge that both Fromm and Acemoğlu emphasise. It requires a social constitution of the greatest possible equality of opportunity, which is also expressed in inclusive institutions in which as many people as possible can contribute their ideas on an equal footing. This is how an innovative economy develops that guarantees both growth and progress.

Fromm deepens this psychological analysis in The Sane Society (1955a), where he describes how modern man increasingly defines himself in terms of his marketability and does not see himself as a human being among other human beings:

„In the process of an ever-increasing division of labour, ever-increasing mechanization of work, and an ever-increasing size of social agglomerations, man himself became a part of the machine, rather than its master. He experienced himself as a commodity, as an investment, his aim became to be a success, that is, to sell himself as profitably as possible on the market. His value as a person lies in his salability, not on his human qualities of love, reason or on his artistic capacities.“ (p. 249)

In classical economics, which also underpins Acemoğlu’s thinking, humans are primarily understood as rational actors: beings who respond to incentives, maximise utility and trade in markets. In this understanding, institutions are good if they provide efficient rules for this framework of exchange. Fromm’s quote makes it clear that this market logic alone is not sufficient to understand successful social developments. True freedom only exists where people can develop their abilities, act with love and reason, and experience themselves as subjects of their own lifew , not as mere objects of the market.

For Fromm, human beings are social, meaning-seeking and emotionally interwoven beings, vulnerable, capable of development and dependent on resonance. In an alienating economic system, he argues, this being can become ill: mentally, socially and spiritually. Institutions must therefore not only be designed according to the logic of efficiency, but must also enable belonging, meaning and autonomy.

While Acemoğlu emphasises the democratic and economic conditions for self-determination, Fromm also focuses on the socio-psychological ability to claim freedoms and make use of them. A progressive society must enable both dimensions: structural economic participation and personal socio-psychological self-development. It needs institutions that are not only functional, but also create the conditions under which people can grow internally and act in solidarity, in which they can develop as human beings.

Both perspectives culminate in a common insight: freedom is not just an idealistic goal, but a benchmark for the quality of social structures. Institutions that enable freedom – politically, economically and psychologically – are the true indicator of sustainable progress.

In a world increasingly shaped by technological systems, this integrative concept of progress is more relevant than ever. For progress is not a linear process, but a balancing act between efficiency and meaning, between innovation and empathy, between structure and subjectivity, which must be shaped sensibly.

Human development and alienation through technology

Central to Acemoğlu and Fromm’s understanding is the idea that human potential does not automatically unfold. It needs favourable conditions: in this context, Fromm speaks of a „productive orientation“ that must be able to realise itself in love, creativity and self-determination. In The Sane Society (1955a), he writes:

„Man must be restituted to his supreme place in society, never being a means, never a thing to be used by others or by himselves. Man used by man must end, and economy must become the servant for the development of man. Capital must serve labor, things must serve life. (…) Man can protect himself from the consequences of his own madness by creating a sane society which conforms with the needs of man, needs which are rooted in the very conditions of his existence.“ (p. 253)

Only when these conditions are met can humans develop themselves and contribute to the productive shaping of their environment. This expresses the ideal form of a productive relationship with the world. In this sense, Acemoglu also emphasises the importance of inclusive institutions that bring talents to bear and structurally ensure participation – only then, he argues, can a society remain innovative and dynamic.

Progress as a human project – technology between growth and dignity

In Power and Progress (2023), Acemoğlu warns against prematurely celebrating technological change as progress. Artificial intelligence, automation and digital systems can increase productivity – but if their introduction is not accompanied by inclusive political measures, they reinforce existing inequalities and power asymmetries. Acemoğlu is one of those who do not predict automatic productivity and progress effects from artificial intelligence, but rather emphasise the prerequisites for this.

Fromm formulated a similar critique decades earlier – long before the digital modern age. In To Have or To Be ? (1976) and other writings, he describes the „megamachine“ of modern industrial society, which functionalises, objectifies and alienates human beings. Where humans are no longer regarded as subjects but as resources, progress loses its human quality. He criticises the fact that in modern industrial society, „progress“ is understood almost exclusively as quantitative growth – whether in production, consumption or speed. In fact, contrary to common preconceptions, economic growth has not predominantly led to more goods and services in quantitative terms, but above all to better ones in qualitative terms. Nevertheless, it can be argued that the „system“ is focused on the permanent improvement of material prosperity. However, according to Fromm, this reduction of the concept of progress to measurable growth ignores the central question of quality of life.

Both thinkers – Fromm with his existential-humanistic view, Acemoğlu with his institutional-economic analysis – show in different ways that technology is ambivalent. It can liberate or subjugate, open up possibilities or tighten control. What is decisive is not the technology itself, but the way in which it is designed, regulated and socially embedded.

Fromm and Acemoğlu share the conviction that human development and social progress are inextricably linked. Technological or economic development that disempowers, devalues or reduces people to their usefulness is not progress – it is regression. Only when freedom, creativity, participation and dignity become integral parts of our institutions and our understanding of work can true innovation succeed.

Progress, they conclude, is not achieved when we become faster, more efficient or more digital, but when human beings are allowed to be the measure of all things. Technology, efficiency and growth are not goals in themselves, but means to an end. The benchmark remains human beings: in their capacity for reason, love, self-development and active participation in shaping a better world.

Technological impact on productivity and humanity using the example of artificial intelligence

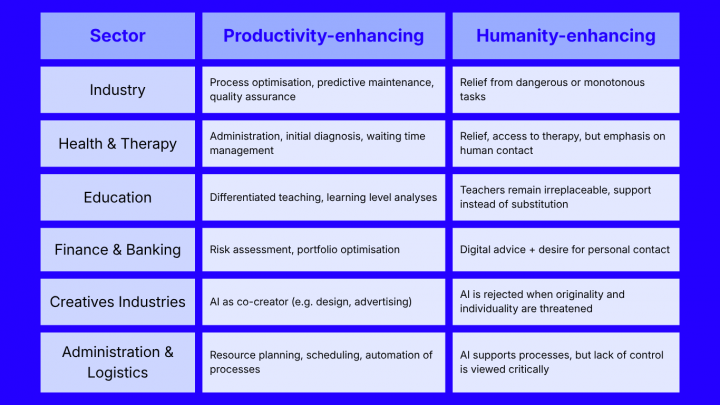

With this in mind, a ongoing student research project was carried out in 2024 at the Business and Law School (BSP) on the Hamburg campus. Students explore the question of how technology (artificial intelligence) can be used in the future to make the world of work both more humane and more productive. The research project is based on the principles of „research-based learning“ according to Ludwig Huber (2013). Twenty-nine qualitative interviews are conducted and evaluated. The following table shows the effects that AI can already have in various sectors.

Table1 : Effects of AI on various sectors

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) has very different effects depending on the industry, both in terms of productivity and humanity. A differentiated view of individual sectors shows that AI is particularly effective when it not only optimises processes but also takes the human dimension into account.

In industry, AI primarily stands for efficiency: it enables predictive maintenance, optimises manufacturing processes and ensures product quality. At the same time, it has the potential to humanise work, for example by relieving employees of monotonous or dangerous tasks. Robots used in welding shops or for heavy load handling protect the health of employees and increase satisfaction.

In the field of health and therapy, AI supports administration, makes initial diagnoses using image recognition, and helps with waiting time management. But it is precisely here that it becomes clear that technology alone is not enough: human closeness, empathy, and trust remain essential. AI can relieve the burden and improve access, but it cannot replace the healing relationship between therapists and patients.

In education, AI is primarily used for personalised learning analyses, differentiated teaching, or adaptive learning environments. This enables teachers to respond more specifically to individual needs. However, it is crucial to note that teachers remain irreplaceable. AI is primarily seen as a supportive tool here, not a substitute.

In the finance and banking sector, AI is used for risk assessment, fraud prevention and portfolio optimisation. Digital assistants are also becoming increasingly important in customer service. Nevertheless, studies and customer experiences show that when it comes to complex or trust-intensive issues, many people still prefer personal contact. AI is valued here as a supplement, not a replacement.

In creative industries such as design, advertising and music, AI is increasingly serving as a co-creator: it can generate designs, suggest variations or combine ideas. But the line between inspiration and threat is a fine one. Where AI appears to undermine originality and individuality, it is rejected. Creativity remains a deeply human process that cannot be fully automated.

AI also contributes to efficiency in administration and logistics – for example, through intelligent resource planning, automated scheduling, or workflow management. Nevertheless, there is ambivalence here: while standardised processes benefit, a lack of control or transparency is often perceived critically. Human intervention remains important – especially when it comes to decisions with social implications.

This sectoral analysis makes it clear that AI can both increase productivity and promote humanity, provided that its use follows ethical guidelines and serves humanity. What is crucial is not only what AI can do, but how it is designed and embedded: technology-supported, but human-centred.

However, AI can only contribute to humanisation if it is embedded in holistic change processes. Acemouglu bases this holism on intuition, while Fromm bases it on social formation. The question „What is progress today?“ is being asked anew: progress is not only what is faster or more efficient, but what empowers people. The integration of creativity, meaning, responsibility and digital innovation into the design of work is not a utopia, but a strategic necessity.

Epilogue: Progress in the service of humanity

Daron Acemoğlu and Erich Fromm share a central concern: securing the conditions for a dignified life in the face of technological and social change. Fromm warns urgently against a concept of progress that is based one-sidedly on technology and economics and loses sight of the human aspect. For him, it is clear that genuine development must be thought of holistically. Advances in productivity or efficiency are not desirable per se – they can even be destructive if they are not accompanied by psychological maturation, social justice and cultural reflection.

Daron Acemoğlu similarly emphasises that technological innovations only have positive effects when they are accompanied by inclusive political and economic institutions. In his latest work, he shows that technological progress all too often falls into the hands of a few and exacerbates social inequalities instead of reducing them – for example, when automation leads to a concentration of power and undermines democratic participation. For Acemoğlu, too, technology is not an end in itself, but a tool that must be put at the service of human development (Acemoğlu & Johnson, 2023).

Both thinkers therefore criticise systems that undermine freedom, creativity and dignity, and both advocate for conditions that enable self-determination, participation and intellectual growth. Their message is highly topical – especially in the context of artificial intelligence, digital transformation and global power shifts. Progress, they agree, should not be measured solely by what is possible, but by what benefits humanity. Especially in times of exponential change, high complexity and uncertainty, and social fragmentation, Fromm and Acemoğlu’s integrated approach can provide important insights into the conditions that need to be created to enable humane and equitable progress. The characteristics of new technologies must meet specific conditions in society in order to result in the desired forms of progress. The research project presented above provides initial indications of what this path might look like.

The joint demand derived here by Acemoğlu and Fromm for universally understood humanity in technological progress – because otherwise it would not be progress at all – is certainly a liberal concern and can also be found, for example, in Amartya Sen (1972) or Frank Knight (1923, 1925). Both Sen and Knight emphasise that the market and freedom are each bound by preconditions and, if these are not met, can lead to excessive rivalry and one-sided materialism. Through and during their participation in the market and competition, humans undergo a dynamic process of personality development and preference formation. Here, too, the abstract-structural interacts with the concrete-individual in a system-specific way. Without humanity, technological development does not necessarily lead to progress, because, according to Acemoğlu and Fromm, economic use inherently involves social and institutional power relations as well as psychosocial and emotional experiences. Critical reflection on this must continually adjust the logic and freedom of the market to the development and freedom of the individual. Only then can progress be achieved.

„And good men – women also – reach good ends. There must, there must, be some that would fit. Ladies and gentlemen, help us look for it!“ (Brecht, 1967)

The full article in German is available here.

She is currently a Professor of Business Psychology at the Business and Law School (BSP) in Hamburg. She is a certified supervisor, coach, and organizational consultant (DGSv), as well as a certified psychosocial online counsellor (DGOB). Her main areas of work and research include creativity and innovation management, research on ageing and care, New Work and AI, as well as qualitative research methods.

Könnte Sie auch interessieren

24. November 2025

Small Is Beautiful 2.0:

How Digital Decentralisation Can Strengthen Democracy

3. November 2025