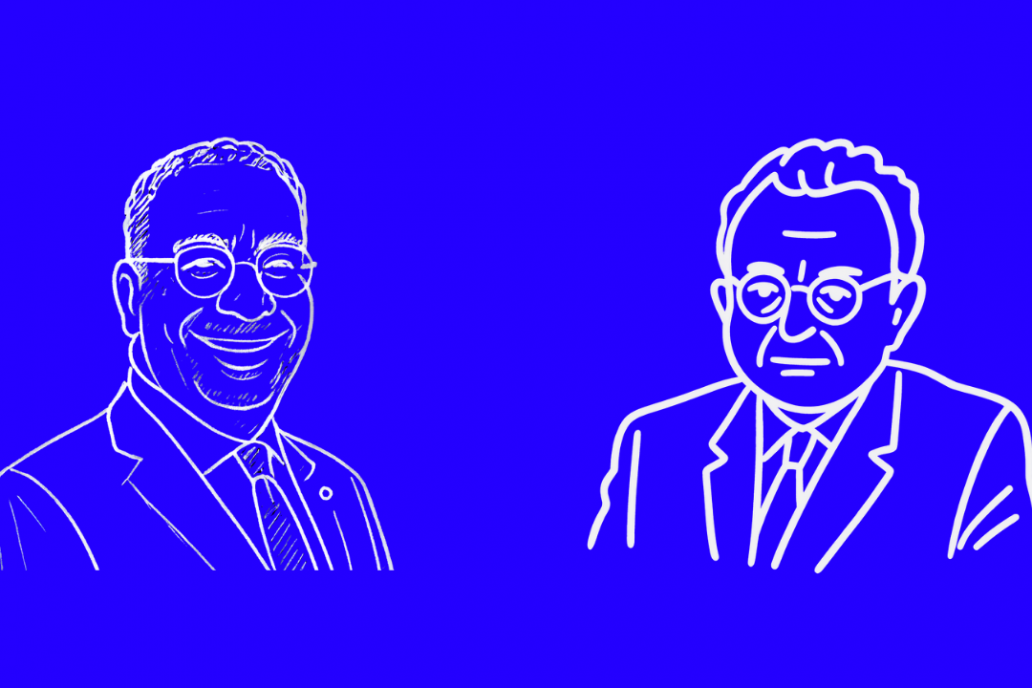

He is a strong voice for European trade relations: in an interview with cep Executive Director Henning Vöpel, the Chair of the European Parliament’s Trade Committee talks about Europe’s geopolitical situation, industrial policy dependencies and progress in competitiveness.

Europe is in a unique situation: the transatlantic alliance has become fragile, Russia’s war of aggression is now in its fourth year, and competition from China is putting pressure on Europe, both with unfair subsidies and with rare earths and economic dependencies. How would you describe the situation for Europe as a whole?

In fact, the global order in the area of trade has changed completely. We are no longer in the era of the World Trade Organisation of 1994, but in a very fragmented situation. Europe is like a ship in a storm, facing headwinds from different sides, and we have to see how we can deal with this. Our response to the new situation must include taking a firm stance towards the US and conducting negotiations for a reasonably stable relationship, as we both have economic interests. With China, we must take measures to curb unfair competition and thus develop our own opportunities. Thirdly, we must strengthen our own industry, promote innovation and advance as a technology leader. And fourthly, precisely because we are predictable and stable, we should work harder to build stable structures with the countries of the Global South.

In your opinion, can this be achieved without resorting to protectionist measures? In its latest issue, The Economist raised the question of whether it is possible to defend oneself against the US and China with tariffs without resorting to such measures oneself.

The European Union is, in fact, more dependent on imports and exports than any other bloc. Many industries would not be viable without markets outside the EU or components supplied from other countries. Protectionism would therefore always carry the risk of marginalising market participants and encouraging other countries to adopt protectionist measures as well. A classic example: we require our trading partners to grant access to public procurement. If we were to do the opposite now, Indonesia, for example, would accuse us of breaking our word. I am also not sure that protectionism leads to greater efficiency or innovation potential in the long term. Studies show that protectionism can have a paralysing effect. I am therefore convinced that we can build stable relationships with other measures such as trade agreements that continue to promote an open and fair market.

And yet it must be said that we have become dependent in many areas. You were involved in the negotiations yourself, and this week the Economic Security Doctrine was passed. Can you briefly outline the most important measures for strengthening Europe’s economic security? After all, these dependencies, including in terms of security and industrial policy, have become very costly.

First, we need to understand why this is the case. It is not only China that is being ‘unfair’; we have also long benefited from China’s low wages and environmental regulations, particularly in the refining of rare earths and lithium. European companies have also abandoned the iron law of commerce that you should have at least two suppliers for a product. This situation is therefore partly our own fault. Now we need to find out where we are particularly dependent and where we are vulnerable – both in industrial development and in the digital sector. We need to develop our own products and software more strongly in this area.

A digital tax?

Perhaps a digital tax should be introduced to generate more resources for these measures. We also need to identify which sectors are particularly sensitive to investment, such as energy infrastructure. In addition, we need to consider more defensive measures, especially with regard to rare earths and raw materials. We need to ask ourselves why mining in Europe takes five years – can’t this be accelerated? And if we consider the battery to be a central element for cars and energy storage, we need to generate the relevant raw materials in Europe itself and recycle much more.

Does Europe need to rethink its trade policy? How can we expand our influence in the countries of the Global South? Does Europe need to become more pragmatic in its negotiations and offer development opportunities on a more equal footing?

Europe has certainly sometimes pointed the finger at world history, but overall Europe is perceived as a reliable and fair partner. We have many examples where we have introduced instruments through trade agreements that promote value creation and employment in partner countries. One example is Chile, where we have introduced a double pricing system for lithium to encourage lithium processing and support investment in sustainable lithium extraction and refining. This has given us an additional supplier, but it also generates added value in Chile. This could even lead to a battery factory or hydrogen production. We are supporting 32 projects for the production of green hydrogen with a total of around 216 million euros – half of these funds are going towards the conversion of the energy supply in Chile, including for a steelworks that is operated using direct reduction with hydrogen. The other half of the budget is used for the production of green hydrogen, which is transported to Europe, specifically to Hamburg. Such partnerships are now also valued by many countries in the Global South.

Trade policy can hardly be separated from security policy and industrial policy anymore. How do you see the future? Do you believe in a return to a rules-based, multilateral order? And what measures must Europe take in terms of security policy and industrial policy?

It is true that Mr Trump has strongly linked trade policy with security and digital policy, and this also highlights Europe’s weaknesses. In terms of security policy, we are not in a position to organise our defence alone, and digitally we have a problem because all cloud storage and data is in the US, which makes us vulnerable to blackmail. The US is exerting considerable pressure on our digital legislation. In my view, however, they are only implementing what should actually be a fundamental principle: everything that is legal offline must also apply online. That is why it is important to compensate for these two weaknesses as quickly as possible. We have said that we need at least three years to do this, but after that we should be on an equal footing and able to negotiate without pressure in both areas – security policy and digital legislation.

One final question: there is the Draghi Report and the Letta Report, both of which have identified shortcomings in competitiveness. How confident are you that we can quickly close the competitiveness gap in order to restore the sovereignty that is needed at this time? I believe that a sovereign Europe is inconceivable without a competitive Europe. That is a key point. However, both reports express disappointment with the progress made in implementing their measures. How optimistic are you that we can close this gap?

It is understandable to feel frustrated when things are not implemented immediately. But if you look at developments over the past year, you can see that competitiveness and innovation are now high on the agenda. We have introduced many laws to simplify bureaucratic processes and accelerate industrial development, particularly in the area of resource extraction. I am convinced that the message has been received, even if progress is sometimes slower than one would like.

This interview is also available in German.

Copyright Header Picture: shutterstock / Copyright: Herder

Könnte Sie auch interessieren

20. November 2025

Work and Society in Transition: a Transdisciplinary Perspective on Progress, Freedom and Humanity in the Thinking of Fromm and Acemoğlu

3. November 2025

How Europe Can Reclaim Its Future: Seven Priorities for a Future-Competent Continent

3. November 2025